The Wall Street Economist

The Wall Street Economist

Dr. Edmond J. Seifried

In 2008-09, the FOMC, the all-powerful policy-making arm of the Federal Reserve System, faced a challenging dilemma. In response to the housing bubble collapse, the Wall Street financial crisis, the bankruptcy of major U.S. automakers, and the looming demise of giant mortgage providers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the FOMC reduced interest rates to the 0.0%-0.25% range. Economists refer to this near-zero range of interest rates as the ‘zero boundary’.

As the FOMC crossed the threshold into the zero boundary, there was a realization that not only was this unchartered territory in the annals of U.S. monetary policy, but that suddenly the arsenal of monetary policy weapons was virtually empty. Sure, the Fed could goad banks into loosening credit standards in an effort to stimulate economic growth through cheerleading and verbal arguments, but real market-changing policies were just not available. In response to this policy crisis, the Fed introduced a revolutionary approach – one that would save the economy from meltdown, but one with unknown consequences.

Today, this policy, officially called Large Scale Asset Purchases (LSAP) or better known as quantitative easing, continues to provide stimulation to markets, housing, employment, and GDP growth. LSAP, which began in 2009 and officially ended in October 2014, injected some $3 trillion of liquidity into the U.S. economy. This liquidity will remain in the economy for many years to come as the FOMC debates how best to remove this liquidity without causing massive market disruptions.

One of the so called channels of the LSAP program – or ways in which the massive injection of liquidity was to aid our ailing economy – was to lower the exchange rate of the U.S. dollar against our trading partners, thereby giving U.S. exporters a price advantage. This assistance was expected to result in a narrowing of the U.S. trade deficit, which held the promise of increased employment opportunities for U.S. workers and higher GDP growth. History demonstrates that the theoretical promise of lower trade deficits did in fact come to fruition. The trade deficit before LSAP was approximately $700 to $800 billion per year; after LSAP, $400 to $600 billion per year. Of course, this turn of events was not lost on our trading partners.

Recently, with economic growths rates in Europe and Japan near zero, the monetary authorities of Europe and Japan have borrowed a page from our playbook. In the early months of 2015, they have instituted, albeit on a smaller scale, their own versions of LSAP. These actions have caused the U.S. dollar to reverse course and strengthen.

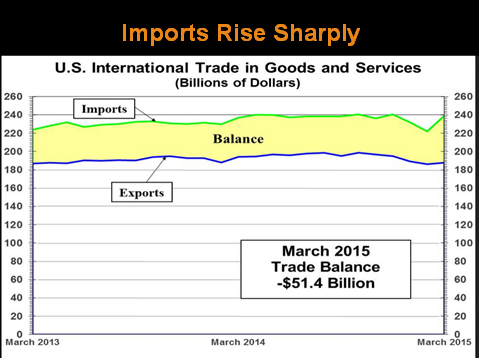

Economic theory predicts that the strengthening of the dollar will lead to lower exports and higher imports for the U.S. economy, causing the trade deficit to widen. Unfortunately, the theoretical predictions are coming true. As the chart shows below, imports surged in March of 2015, increasing our trade deficit from $35.9 billion in February to $54.1 billion in March.

Source: United States Census Bureau

Source: United States Census Bureau

Dr. Ed Seifried is Chief Economist and Strategic Advisor at BNK Advisory Group. He is also professor of economics and business at Lafayette College in Easton, PA, and a faculty member of numerous graduate banking schools, including Stonier Graduate School of Banking and the Graduate School of Retail Bank Management. He also serves as dean of The West Virginia and Virginia Banking Management Schools. Dr. Seifried is a nationally recognized speaker and is the author of both academic and popular articles and books. He is the co-author of BNK's Art of Strategic Planning in Community Banks and The Art of Risk in Community Banks, a series for the committed bank director. He holds his doctorate in economics and business from West Virginia University.

© Northwest Farm Credit Services 2015

Stay up to date

Receive email notifications about Northwest and global and agricultural and economic perspectives, trends, programs, events, webinars and articles.

Subscribe