The Northwest is one of the primary onion-producing regions in the U.S. Onions from the Northwest are fresh packed or processed by large, vertically integrated farms and privately owned packinghouses. From September to May, Northwest onion producers supply

major markets, with most of their fresh product moving east to the larger population centers. Some of their crop is exported.

Production

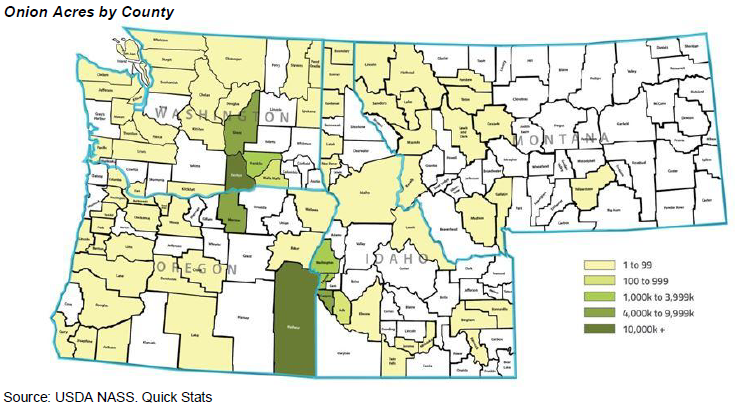

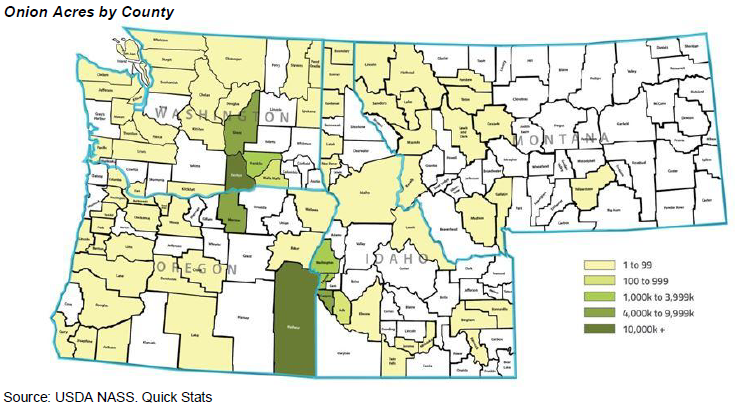

More than 150 countries worldwide produce onions, with approximately 79.7 million tons grown on 9.1 million acres. The most recent global production data from 2013 show that India leads onion production, followed by China, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Russian Federation. The U.S. ranks 16th in global production. In 2017, U.S. farmers planted 138,000 acres of onions. Thirty-seven percent of those acres - 51,600 - were in Washington, Idaho and Oregon.

In the Northwest, the bulk of onion production comprises two regions: the Treasure Valley in Western Idaho and Eastern Oregon, and the Columbia Basin in Central Washington and North Central Oregon. Other Northwest production areas include Western and Central Oregon and Walla Walla, Washington. Walla Walla farmers produce 1,200 acres of Walla Walla Sweets, a niche salad variety in the expanding global sweet-onion industry. The vast majority of the Northwest's onion production is of the summer storage variety. In 2017, Northwest onion production totaled more than 34 million cwt.

Irrigation differs between regions. Locations with well water and direct access to river water benefit from fewer water impurities compared to water from canals. Sprinkler irrigation results in more potential for bacterial damage in the necks of the onions.

Value Chain

Onions are marketed as either fresh or processed. Fresh-onion consumption includes home and foodservice uses. Processed onions are most commonly frozen or dehydrated; they are also canned or included in other food products. Large, vertically integrated producers may conduct marketing. Growers may also sell onions directly to a packing shed, which provides services that may include post-harvest handling, packing, cooling and transportation. In both marketing processes, bulbs are sorted and packed mainly into 50-pound sacks or into consumer-friendly packages.

The market for fresh and processed onions leverages a combination of open marketing and contract pricing. Some processors and fresh-pack processors seek to forward contract a portion of their annual inventory supply. Early contract negotiations begin to establish market expectations for each crop year and contract pricing offers some market risk protection to producers, packers and processors. However, because the majority of onions are sold into the fresh market, open-market pricing drives the onion market.

The onion market can be volatile. Prices often change dramatically with small shifts in supply. The unique seasonality and storability of onions add to their market volatility and price variance. Most onions grown in the United States have a limited storage life of one to two months. However, onions grown in the Northwest are exceptional because they can be stored generally from six to eight months, depending on the type of onion and the storage facility. This allows onions from the Northwest to be marketed from September through April.

Idaho and Eastern Oregon onions are marketed under a federal marketing order that authorizes grade, size and pack regulations. Most other onion-producing areas in the United States do not operate under a marketing order. Given the disparity of onion-growing regions across the United States and the onion industry's propensity to be less organized than other commodities, total seasonal production is frequently difficult to assess. Accordingly, even the perception of oversupply or undersupply in the market can have a marked effect on prices.

Growth in the size of the marketing companies selling fresh onions will continue. Consolidation at the retail and foodservice level is resulting in a demand for larger sales organizations that can provide larger volumes of produce and be able to source produce for periods that often exceed local marketing seasons.

Industry Drivers

Onion Demand

Demand for fresh produce in the U.S. continues to increase. Per capita onion consumption rose 70 percent between 1982 and 2014, increasing from 12.2 pounds to 20.6 pounds. Factors driving demand include consumers' interest in healthy diets, increased use of onions in ready-made meals, and onions' popularity among Asian and Hispanic consumers, the fastest growing racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. whose diets include more fresh produce than the general population.

Onion Breeding/Varieties

Advances in onion breeding are creating varieties with improved yields and storability. Depending on the variety, breeding enhancements include uniformity in round bulbs or foliage that performs well under heat stress and has an increased bolt tolerance (resistance to premature flowering) and storage potential, with some varieties storing up to six months. Varietal improvements provide growers opportunities in new and different growing practices, market segments and pricing windows.

Storage and Packing

Producers' opportunities for pricing onions throughout the marketing season are largely dependent on storage and packing. Onion storage facilities are investing in technologies to extend onions' storability. Common storage enhancements include airflow, climate control and cold storage. Onion packing lines are increasingly automated, which reduces labor, lowers expenses and increases capacity and quality control. Together, storage and packing enhancements position Northwest onions to better complement markets in California, Texas, Mexico and South America.

Irrigation

Drip irrigating onions was introduced approximately 20 years ago in the Columbia Basin. Today, more than a third of Columbia Basin onion growers use drip irrigation, while adoption in the Treasure Valley is increasingly popular. Benefits of drip irrigation include lower fertilizer costs; significant reductions in water use and nitrate leaching; increased control of insects, iris yellow spot virus and weeds; and increased onion size and marketable yield. Tradeoffs include added costs and increased attention to irrigation system design and maintenance.

Appendix A

Best Practices

To survive in competitive industries, onion producers must focus on many business aspects at once. Basic production factors such as planter spacing, irrigation timing and weed management are necessary to grow a good crop, but additional actions can help ensure long-term viability in an industry and even provide a competitive edge. Best practices for row crops are grouped by their area of applicability and include production, marketing, labor management and cost containment.

Production

Onion producers and industry specialists have worked closely to develop practices and technologies that will increase yield and/or quality. Best practices in production include:

Another best practice is the ability to effectively manage the thrip population that spreads the iris yellow spot virus. Best practices in thrip management include timely and aggressive applications of insecticides, field selection that distances onion production from thrip habitat and longer crop rotations.

Marketing

Few row crop producers are large enough to take on the challenge of marketing their own crops directly to the consumer, so most producers rely on a processor or fresh packing facility to take care of marketing. However, producers can increase the demand and marketing potential of their crops by using the following strategies.

Differentiation: Onion producers can differentiate their crops in the marketplace. Changing production methods to certify crops as organic, or working with processors to grow specialty varieties such as Walla Walla Sweet onions, are examples of differentiation.

Vertical integration: Onion grower groups and producers have invested in fresh-packing facilities and others have expanded into processing or dehydrating facilities.

Each of these options may have the potential to increase revenue, reduce costs or even maintain a market for growers. However, each also has the potential to dilute capital and push an individual or grower group beyond core competencies, so producers must carefully evaluate available opportunities.

In the case of fresh-onion integrated operations, capturing packing revenues helps hedge against price variability. In the Columbia Basin, most independent fresh-onion growers are also packers. Onion packers must be cost competitive and represented by or operate a best-of-class marketing desk.

Labor Management

Best practices in successful labor management focus on strategies to retain better-educated and trained workers by:

Managing costs remains a critical component in guiding an operation toward profitability. Best practices in this area include:

Long-term success requires that onion producers be superior growers and sound business managers who proactively and creatively manage production expenses, labor and marketing.

Appendix B

Glossary

Fresh-pack processors - Fresh-pack sheds are focused on packaging certain sizes of onions normally in 50-lb bags. Although smaller consumer packs are becoming more prevalent, they have yet to overtake the normal 50-lb bag production. Fresh-pack sheds sell to retailers, brokers and restaurants. The majority of onion sizes packaged include medium (2"-3 1/4"), Jumbo (3" and up), Colossal (3 3/4" and up) and Super Colossal (4 1/2" and up). Smaller sizes are used in some cases but are not as common.

Iris yellow spot virus - Virus transmitted by onion thrips, which are tiny, milky-white insects. Symptoms include yellow- to straw-colored lesions on leaves. Once the virus takes hold it brings down and kills the whole plant. Iris yellow spot virus affects yield and quality of final product.

Vertical integration - Alignment of agricultural business ventures concerning crop production beginning with planting to growing, harvesting, storage, processing and marketing of a commodity

Yellow bulb onion - The majority of varieties grown in the Treasure Valley are yellow onions. Varieties include but are not limited to Vaquero, Joaquin, Granero and 1600. Yellow varieties make up about 87 percent of the total crop produced. Yellow onions can also be referred to as sweet onions.

Production

More than 150 countries worldwide produce onions, with approximately 79.7 million tons grown on 9.1 million acres. The most recent global production data from 2013 show that India leads onion production, followed by China, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Indonesia, Vietnam and the Russian Federation. The U.S. ranks 16th in global production. In 2017, U.S. farmers planted 138,000 acres of onions. Thirty-seven percent of those acres - 51,600 - were in Washington, Idaho and Oregon.

In the Northwest, the bulk of onion production comprises two regions: the Treasure Valley in Western Idaho and Eastern Oregon, and the Columbia Basin in Central Washington and North Central Oregon. Other Northwest production areas include Western and Central Oregon and Walla Walla, Washington. Walla Walla farmers produce 1,200 acres of Walla Walla Sweets, a niche salad variety in the expanding global sweet-onion industry. The vast majority of the Northwest's onion production is of the summer storage variety. In 2017, Northwest onion production totaled more than 34 million cwt.

Irrigation differs between regions. Locations with well water and direct access to river water benefit from fewer water impurities compared to water from canals. Sprinkler irrigation results in more potential for bacterial damage in the necks of the onions.

- In Washington, production is largely under sprinkler irrigation. To mitigate potential damage, growers are implementing more drip irrigation.

- In the Treasure Valley, most onions are grown under furrow or drip irrigation because the large yellow onions grown there are particularly susceptible to bacterial damage in the necks.

Value Chain

Onions are marketed as either fresh or processed. Fresh-onion consumption includes home and foodservice uses. Processed onions are most commonly frozen or dehydrated; they are also canned or included in other food products. Large, vertically integrated producers may conduct marketing. Growers may also sell onions directly to a packing shed, which provides services that may include post-harvest handling, packing, cooling and transportation. In both marketing processes, bulbs are sorted and packed mainly into 50-pound sacks or into consumer-friendly packages.

The market for fresh and processed onions leverages a combination of open marketing and contract pricing. Some processors and fresh-pack processors seek to forward contract a portion of their annual inventory supply. Early contract negotiations begin to establish market expectations for each crop year and contract pricing offers some market risk protection to producers, packers and processors. However, because the majority of onions are sold into the fresh market, open-market pricing drives the onion market.

The onion market can be volatile. Prices often change dramatically with small shifts in supply. The unique seasonality and storability of onions add to their market volatility and price variance. Most onions grown in the United States have a limited storage life of one to two months. However, onions grown in the Northwest are exceptional because they can be stored generally from six to eight months, depending on the type of onion and the storage facility. This allows onions from the Northwest to be marketed from September through April.

Idaho and Eastern Oregon onions are marketed under a federal marketing order that authorizes grade, size and pack regulations. Most other onion-producing areas in the United States do not operate under a marketing order. Given the disparity of onion-growing regions across the United States and the onion industry's propensity to be less organized than other commodities, total seasonal production is frequently difficult to assess. Accordingly, even the perception of oversupply or undersupply in the market can have a marked effect on prices.

Growth in the size of the marketing companies selling fresh onions will continue. Consolidation at the retail and foodservice level is resulting in a demand for larger sales organizations that can provide larger volumes of produce and be able to source produce for periods that often exceed local marketing seasons.

Industry Drivers

Onion Demand

Demand for fresh produce in the U.S. continues to increase. Per capita onion consumption rose 70 percent between 1982 and 2014, increasing from 12.2 pounds to 20.6 pounds. Factors driving demand include consumers' interest in healthy diets, increased use of onions in ready-made meals, and onions' popularity among Asian and Hispanic consumers, the fastest growing racial/ethnic groups in the U.S. whose diets include more fresh produce than the general population.

Onion Breeding/Varieties

Advances in onion breeding are creating varieties with improved yields and storability. Depending on the variety, breeding enhancements include uniformity in round bulbs or foliage that performs well under heat stress and has an increased bolt tolerance (resistance to premature flowering) and storage potential, with some varieties storing up to six months. Varietal improvements provide growers opportunities in new and different growing practices, market segments and pricing windows.

Storage and Packing

Producers' opportunities for pricing onions throughout the marketing season are largely dependent on storage and packing. Onion storage facilities are investing in technologies to extend onions' storability. Common storage enhancements include airflow, climate control and cold storage. Onion packing lines are increasingly automated, which reduces labor, lowers expenses and increases capacity and quality control. Together, storage and packing enhancements position Northwest onions to better complement markets in California, Texas, Mexico and South America.

Irrigation

Drip irrigating onions was introduced approximately 20 years ago in the Columbia Basin. Today, more than a third of Columbia Basin onion growers use drip irrigation, while adoption in the Treasure Valley is increasingly popular. Benefits of drip irrigation include lower fertilizer costs; significant reductions in water use and nitrate leaching; increased control of insects, iris yellow spot virus and weeds; and increased onion size and marketable yield. Tradeoffs include added costs and increased attention to irrigation system design and maintenance.

Appendix A

Best Practices

To survive in competitive industries, onion producers must focus on many business aspects at once. Basic production factors such as planter spacing, irrigation timing and weed management are necessary to grow a good crop, but additional actions can help ensure long-term viability in an industry and even provide a competitive edge. Best practices for row crops are grouped by their area of applicability and include production, marketing, labor management and cost containment.

Production

Onion producers and industry specialists have worked closely to develop practices and technologies that will increase yield and/or quality. Best practices in production include:

- Managing crop rotations to four or more years between particular row crops

- Implementing GPS-based tillage, planting, cultivation and yield monitoring

- Using variable-rate fertilization to enhance production efficiency

- Protecting consumers and raw commodities by adopting phytosanitary practices that prohibit the spread of plant pests or pathogens

- Applying regular and focused pesticide and herbicide

- Incorporating expertise from industry experts such as seed company representatives, fertilizer and chemical representatives, agronomists, university extension agents, etc., to increase overall knowledge and decision-making effectiveness

- Efficient water delivery to the plant's root zone

- Uniform moisture level throughout the field

- Efficient chemical application, reducing nitrogen costs by as much as 40 to 50 percent

- Reduction in total water usage

- Less soil erosion

- Increased yields, and yields of a more uniform size

- Adaptation to fields with irregular field patterns, rolling topography or marginal soils

- Reduced water contact with crop leaves, making conditions less favorable for disease

- Better moisture control that allows for more timely ground spraying

Another best practice is the ability to effectively manage the thrip population that spreads the iris yellow spot virus. Best practices in thrip management include timely and aggressive applications of insecticides, field selection that distances onion production from thrip habitat and longer crop rotations.

Marketing

Few row crop producers are large enough to take on the challenge of marketing their own crops directly to the consumer, so most producers rely on a processor or fresh packing facility to take care of marketing. However, producers can increase the demand and marketing potential of their crops by using the following strategies.

Differentiation: Onion producers can differentiate their crops in the marketplace. Changing production methods to certify crops as organic, or working with processors to grow specialty varieties such as Walla Walla Sweet onions, are examples of differentiation.

Vertical integration: Onion grower groups and producers have invested in fresh-packing facilities and others have expanded into processing or dehydrating facilities.

Each of these options may have the potential to increase revenue, reduce costs or even maintain a market for growers. However, each also has the potential to dilute capital and push an individual or grower group beyond core competencies, so producers must carefully evaluate available opportunities.

In the case of fresh-onion integrated operations, capturing packing revenues helps hedge against price variability. In the Columbia Basin, most independent fresh-onion growers are also packers. Onion packers must be cost competitive and represented by or operate a best-of-class marketing desk.

Labor Management

Best practices in successful labor management focus on strategies to retain better-educated and trained workers by:

- Improving working conditions

- Providing competitive compensation and benefits packages

- Adapting to workers' flexible scheduling needs

- Increasing automation/scale in equipment and other processes

Managing costs remains a critical component in guiding an operation toward profitability. Best practices in this area include:

- Careful budgeting and variance monitoring

- Purchasing alliances to take advantage of volume discounts

- Overall cost control, offsetting increases in one area with reductions in another

Long-term success requires that onion producers be superior growers and sound business managers who proactively and creatively manage production expenses, labor and marketing.

Appendix B

Glossary

Fresh-pack processors - Fresh-pack sheds are focused on packaging certain sizes of onions normally in 50-lb bags. Although smaller consumer packs are becoming more prevalent, they have yet to overtake the normal 50-lb bag production. Fresh-pack sheds sell to retailers, brokers and restaurants. The majority of onion sizes packaged include medium (2"-3 1/4"), Jumbo (3" and up), Colossal (3 3/4" and up) and Super Colossal (4 1/2" and up). Smaller sizes are used in some cases but are not as common.

Iris yellow spot virus - Virus transmitted by onion thrips, which are tiny, milky-white insects. Symptoms include yellow- to straw-colored lesions on leaves. Once the virus takes hold it brings down and kills the whole plant. Iris yellow spot virus affects yield and quality of final product.

Vertical integration - Alignment of agricultural business ventures concerning crop production beginning with planting to growing, harvesting, storage, processing and marketing of a commodity

Yellow bulb onion - The majority of varieties grown in the Treasure Valley are yellow onions. Varieties include but are not limited to Vaquero, Joaquin, Granero and 1600. Yellow varieties make up about 87 percent of the total crop produced. Yellow onions can also be referred to as sweet onions.

Stay up to date

Receive email notifications about Northwest and global and agricultural and economic perspectives, trends, programs, events, webinars and articles.

Subscribe