September 29, 2020

Introduction

The U.S. was the world’s third-largest commercial producer of sweet and tart cherries until 2020 when China’s increased acreage finally led to them outpacing U.S. production. The European Union and Turkey, the world’s largest commercial producers, each account for nearly 25% percent of production.1National production and acreage of sweet cherries is concentrated on the west coast. Washington leads the nation with around two-thirds of the production while Oregon and California each account for a little under 20%.2

Few places in the world possess the microclimate necessary to grow quality sweet cherries. The irrigated volcanic soils of the Northwest, combined with the region’s ideal climate conditions and horticultural techniques, produce a superior sweet cherry that continues to provide a competitive advantage to growers.

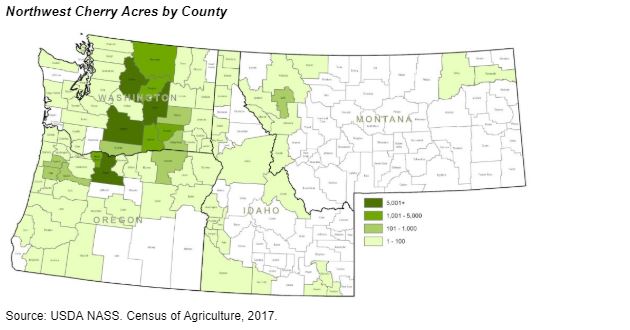

The Yakima Valley and Wenatchee Valley regions of Washington, and Willamette Valley and The Dalles/Hood River areas of Oregon, dominate cherry production in the Pacific Northwest.

Varieties

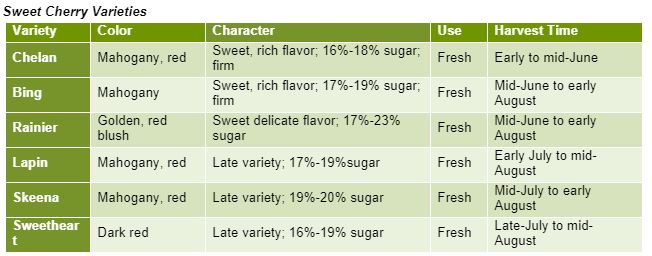

The bulk of the Northwest’s red cherry production is comprised of Bing, Sweetheart, Skeena, Chelan, Tieton, Lapin and Lambert varieties. Over the past several years the Northwest sweet cherry season has become longer and later due to the introduction of varieties, such as Sweetheart and Skeena, that favor high elevations. At 8 to 10 tons per acre, and sometimes up to 18 tons with high density plantings, these varieties outperform others, which typically yield 6 to 8 tons per acre.

Additional information about cherry varieties is available via www.nwcherries.com

Source: Northwest Farm Credit Services.

Value Chain

Growth and HarvestCherry trees grow from rootstock. Although some orchards grow their own rootstock, most rootstock is established in nurseries. Rootstock is selected based on qualities that make growth successful, such as anchorage and resistance to pests and diseases. Rootstock grows in the field for about a year. Then, specific cherry tree varieties are grafted onto rootstock and grown in a nursery until ready for replanting in an orchard, usually within a couple of years.

Once a cherry tree is planted in an orchard it’s considered pre-productive until it produces a crop; this usually takes a couple more years. Full production happens at around three to four years depending on many variables such as variety, soil and growing methods. Growers with high-quality soil will sometimes move the tree to a trellis system after the first few years in the orchard.

The primary reason for trellis systems is to facilitate high-density orchards. Traditionally, a cherry orchard had 500 trees per acre. Today, 1,500 to 2,000 trees can be planted per acre using a trellis system. Trees are planted at various spacings, then limbs are trained on wires to fill space between trees. This results in higher-density trees allowing higher yields per acre, faster picking and larger payments for the pickers.

The upright fruiting offshoot (UFO) trellis system is used for cherry trees. With this system, young cherry trees are planted at an angle and trained to grow on a two-dimensional plane, putting more of their effort into developing a fruiting wall instead of the nonproductive wood typical of a traditional, three-dimensional canopy.

Before harvest, in the spring growers occasionally thin blossoms to achieve ideal fruit size. Harvest starts in late May/early June and runs through mid- to late August. Because cherries are delicate and susceptible to damage and bruising, harvest is done by hand. They are usually picked into small buckets and eventually placed into bins that hold around 300 to 400 pounds.

Weather can pose challenges to cherry harvest. The following weather events can compromise cherry quality:

- Frost in and around bloom time.

- Wind that blows cherries into one another, branches or the tree, causing bruising.

- Hail and rain that knocks cherries off trees.

- Rain that settles near the stem causing the fruit to split.

- Excessive heat and sunburn

After harvest, cherries are sent to a packing warehouse where they are washed, sorted and packed for retail. The Northwest’s two main packing hubs are in Yakima and Wenatchee, both in Washington. Packing warehouses sort by size and grade and cull out off-grade fruit, but do not store fruit for long periods of time due to cherries highly perishable nature. Therefore, packing delays can severely impact cherry-crop quality.

Packing lines are increasingly automated, reducing manual labor and improving consistency and quality. With technology upgrades, packing lines can sort for cherries’ size, color, grade, external defects and internal condition. These characteristics determine whether a cherry will be fresh packed or culled. The most desirable size, firmness and color of cherries going to fresh pack fetch the highest premiums.

Large fruit-packing warehouses are generally vertically integrated through purchase of orchards or production-packing agreements with large, independent fruit growers. Advantages include increased control of supply. Cherry packers need 3,000 to 5,000 tons for mechanical sizing lines and around 10,000 tons annually to capitalize on new optical-technology lines.

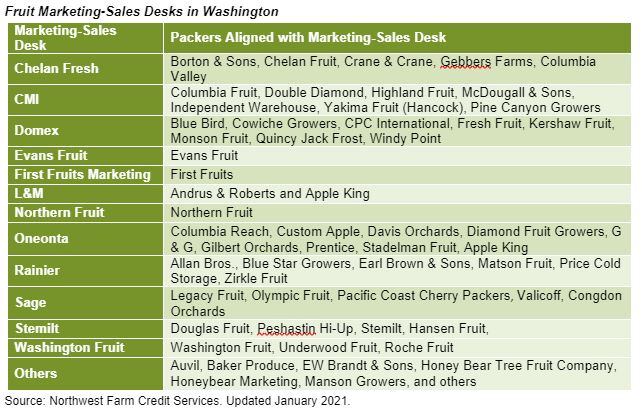

Alignment between growers and packers is not the only place the cherry industry has consolidated tasks under one roof. Several packing warehouses sell their own fruit, or more commonly sell through the marketing-sales desks of another packing warehouse.

Marketing-Sales Desks

The domestic tree-fruit market is dominated by large retail grocery chains. Chains prefer to purchase fruit from operations with the size and scope to supply a large number of stores with high-quality fruit. This has driven packing warehouses to join marketing-sales desks to collectively meet large retail firms’ needs. As a result, the Northwest tree-fruit industry is consolidated down to less than 30 marketing-sales desks, with the 10 largest moving the bulk of the fruit produced.

Retailers

When they are in season and growing conditions are favorable, cherries can be one of the most profitable fruits sold at retail. Accordingly, retailers and packers make concerted efforts to extend the fresh cherry season. Many large marketing-sales desks run cherry programs and promotions to remain attractive to retail customers. Most marketing-sales desks attempt to bring predictability and order to the marketing season with retailer ad campaigns.

The success of the Northwest cherry marketing season depends on a number of factors.

- The length of the marketing season cannot be compressed due to weather or packing capacity. Pricing is typically lowered to move large crop volumes. When a glut of cherries overwhelms the industry’s infrastructure, some cherries may not be sold, prices decline and product quality may suffer.

- An orderly transition from the California crop to the Northwest crop is beneficial. If California is still harvesting when the Northwest begins harvest, there will be an overlap. Lack of a transition period, or gap, often results in lower prices for Northwest cherries.

- A consistent supply of high-quality fruit must be delivered throughout the marketing season. Disruptions in supply will often cause retailers to move away from cherry promotions to other produce.

- The Northwest cherry industry needs to have significant tonnage harvested, packed and shipped prior to the Fourth of July. The holiday represents an optimum time for retail promotions and helps to set the tone for the remainder of the season.

Drivers

Northwest Production TrendsCherry growers are increasing output per acre while decreasing variability in production volumes. Increased acreage, higher-density plantings and updated cherry varieties that provide better quality, consistency and yield potential have resulted in record crops. Cherry crop size is expected to continue increasing due to the development of new varieties capable of producing more than 12 tons per acre and the renewal of acreage from older Bing/Rainier blocks to higher-density, modern strains.

Labor

Since cherries are harvested by hand, finding adequate labor is a persistent concern. Labor scarcity drives labor costs higher; growers and packers continue to look for ways to cut costs by deploying labor resources efficiently and adopting systems and practices that reduce labor needs.Sourcing Labor

Historically, orchardists relied on word of mouth and returning workers to fill their labor needs. However, a more proactive approach is now required. Orchardists are competing for and retaining workers by raising wages, working with labor contractors and keeping well-maintained labor camps.

The H-2A Temporary Agricultural Worker program provides an outlet for attracting and retaining labor. However, the program is costly, and requirements are complex. Program participation requires employers to provide transportation from country of origin, housing, transportation to and from work, and a place to prepare or furnish meals. The employer must guarantee employment for at least 75% of the contracted workdays. Vertically integrated operations have the opportunity to spread costs associated with the H-2A program over a longer working season by transitioning from pruning to packing.

Orchard Management Techniques

Producers can alter growing practices, techniques and management styles to better accommodate workers and improve labor efficiencies. Producers who diversify their operations with multiple varieties, sites, elevations, etc., not only reduce crop risk, but extend production and harvest seasons. An extended harvest season requires fewer workers over longer periods of time.

Advancements in blossom-thinning practices allow producers to effectively manage fruit size profiles as well as enhance crop estimation. Blossom-thinning is an increasingly important tool for the industry to manage supply and help mitigate over-supplied markets. Fruit trees start to develop the following seasons crop during the current bloom, therefore, blossom-thinning will affect the size of the following year’s crop making it viable that orchardists get it right, not too much and not too little.

Harvest-timing technologies are also used by producers to manage harvest activities and labor resources efficiently, reducing labor requirements while also positioning for larger crops.

Impact of Growing Conditions on Labor

Growing-season conditions affect the harvest window and labor needed. Compressed harvest seasons affect the number of workers available. If an entire region is experiencing a light crop, the majority of the workforce may bypass an orchard completely for more productive areas. The adoption of high-density plant spacing and trellis systems allows workers to be more efficient in harvest, creating increased earning potential for both the worker and the producer.

An extended bloom may lead to inconsistent fruit ripening, which can necessitate additional harvest passes through the same acreage. Other adverse weather such as frost, excessive heat, wind, rain and hail can affect the quality of the fruit to be harvested, creating a need for intensified field sorting or selective picking. These can significantly increase labor costs and affect profitability.

Market

Global TradeThe bulk of Northwest tree-fruit crops are sold in the domestic market. However, global markets still play an important role. Canada and China are the largest importers of U.S. cherries. The trade war with China that started in 2018 has negatively impacted U.S. cherry exports to China. However, U.S. cherries are highly desirable in China and consumers remain willing to pay premiums for our superior cherries.

Technology

Technological advances in the tree-fruit industry are driven by the need to maximize labor, monetary and natural resources, while increasing yields and productivity. The cost of technology is significant, but producers reap substantial economic rewards when proven technologies are implemented as part of an overall business strategy.

Producer

GPS and variable-rate technologies for fertilizer and water applications continue to gain acceptance among tree-fruit producers. The need for increased oversight in water management has also promoted increased use of digital drip irrigation systems that can be controlled remotely with technologies such as smart phones or tablets.

The use of shade cloth is less common in cherries than some other tree fruits; however, some late season cherry growers may utilize the product.

The use of drones continues to expand, improving the availability and quality of data for orchard managers. An array of camera and sensor options provides detailed analysis including the identification of soil, moisture, erosion and temperature conditions. Adoption of drone technology will likely increase in the coming years as producers increase focus on precision agriculture.

Packer

Packing technology comes at a significant cost and requires a high level of throughput to support higher fixed costs. Consumer demand and expectations for consistent product require improved technology as a cost of maintaining competitiveness within the industry.

Packing-line technology has expanded over the last several years to include sorting for internal defects, color and size, which provides consumers higher-quality products by minimizing human error. Cameras and highly sophisticated software programs work faster than human hands, leading to significant labor cost savings. Also, throughput capacity is not compromised when sorting through a hail- or other weather-damaged crop. Precise sorting technology captures gradable fruit from a lot that would historically have been entirely culled or downgraded a size, thereby securing the highest possible returns for a producer.

Labor challenges also support the implementation of digital sorting technology. Warehouses are often challenged to keep packing lines fully staffed, particularly during harvest, when employees are recruited for orchard work. The elimination of human sorters on the front end of the packing line often reduces labor needs by 30% to 40% at the warehouse. However, the savings from cutting labor costs are generally offset by increased fixed costs associated with building modifications to accommodate larger lines and increased depreciation costs.

Robotic palletizing also cuts down on labor requirements and increases worker safety, eliminating the need to manually lift and transport heavy bins, boxes and crates.

Appendix A

Best Practices

The following summarizes the best practices common among successful and progressive tree-fruit growers and processors. These primarily relate to issues of production and warehousing.Orchard Production Best Practices

Have a strategic plan- Successful businesses have defined goals and are continually in the process of executing specific strategies in their business. These strategies may include growth (e.g., diversification, replication, integration, networking), downsizing/rightsizing or intensifying (i.e., improving efficiency).

- Growers increase gross revenue through a combination of reaping high yields, producing desirable fruit varieties and peaking on a demanded size profile. A desirable varietal mix and high-yielding orchard structures will continue to be critical to competitive top-line revenues.

- Growers manage fixed and variable expenses, which allows for lower break-even levels.

- Growers with high-density plantings may have a higher cost structure than the average grower, but cost containment remains pertinent as supplies reduce prices in large crop years and the industry becomes increasingly competitive.

- Focusing on orchards of an economic size is key to long-term cost competitiveness.

- Growers achieve diversification by growing multiple types and varieties of fruit.

- Successful growers diversify, when possible, by cultivating crops in differing geographic areas to hedge against widespread weather-related adversity.

- Growers use available risk-management tools, such as crop insurance, to mitigate the risk of adverse and unforeseen events that could drastically affect the business. Crop insurance options include three variations of coverage: production based, revenue based and named peril. Most producers use some combination of these products to tailor a protection strategy that matches the specific safety needs of their business.

- Orchard renovation not only allows for updated orchard structure (i.e., denser plantings and/or trellis systems), but also allows orchards to avoid varietal strain obsolescence.

- Areas where production is struggling need to be updated. Approximately 15+ percent of total planted acres on average may be pre-productive at any one time.

- When their operations lack critical mass, successful producers align with other growers to attract picking crews and assure them of a consistent supply of work that extends from the start of cherry through the end of apple harvest. Access to a dependable labor force will continue to be an important piece of orchard production going forward.

- Growers also might partner with other growers to leverage volume discounts for equipment, chemicals, fertilizers, fuel and other necessary inputs.

- Successful growers align with successful packing or storage warehouses that provide competitive services at reasonable costs. These warehouses need to have quality facilities and current fruit-handling and -packing equipment. Growers who align with successful warehouses tend to perform with more consistent profitability.

- Successful growers place fruit with packing and storage warehouses aligned with a strong sales desk. This provides ready access to large domestic and international retail markets, which translates into the most competitive returns.

- Successful fruit growers have established and implemented a labor strategy for their business that will ensure their seasonal labor needs are met.

- Progressive tree-fruit growers need to be prepared to furnish housing and year-round employment as a means of retaining key employees.

- To help alleviate labor shortages during peak harvest times, producers have begun planting several varieties at different locations or elevations. This creates varied harvest times and a steadier labor-demand window.

- Larger producers are able to move labor forces from one orchard to another over larger geographic areas to ensure the labor force is retained.

- Many producers are successfully using the H-2A Temporary Agricultural Worker program. Although somewhat expensive, the program provides a feasible solution to labor needs.

- Some producers have successfully used contractors who, for a fee, offer full-service labor. However, this practice has met some resistance, mostly because of timing and scheduling considerations.

- Development of labor-reducing or 'picker-friendly' tree-planting styles is proving to be an advantage in terms of the ability to attract and retain an adequate labor supply.

- Successful operations use accrual-based reporting to assess true financial position and performance. These growers also use enterprise accounting to assess profitable and unprofitable business units, or orchard blocks.

- Orchardists with strong liquidity and lower leverage are able to absorb market down cycles and take advantage of strategic opportunities.

- A business should assess the adequacy of its financial position annually by using tools such as financial ratios, peer financial benchmarks and historical trend analyses.

- Stress case scenarios may also be used to give an accurate picture of the true financial position of the business given possible adverse scenarios.

Warehousing Best Practices

Have a strategic plan- Successful businesses have goals and are continually in the process of executing specific strategies in their business. These strategies may include growth (e.g., diversification, replication, integration, networking), downsizing/rightsizing or intensifying (i.e., improving efficiency).

- Successful warehouses maximize use of fixed assets.

- Improved use results in reduced per-unit costs, which enables warehouses to maintain competitive grower returns.

- Warehouses, as processing entities, must contain fixed and variable costs to maintain competitive packing charges and maximize income levels.

- Cost containment allows a warehouse to reduce the level of throughput needed to break even in short crop years when fruit supplies are more scarce than usual.

- Allied packing warehouses trade packing and storage capacity to use assets to their fullest potential. This situation is most often seen with warehouses using a common sales desk.

- Aligned warehouses can dedicate a specific line to a particular variety, with fewer changeovers.

- Sharing and balancing storage needs, improving the variety and size profile of manifest for sales desks and working together to realize increasingly efficient logistics and distribution are inherent advantages of partnership.

- Successful packing warehouses align with sales desks that have steady access to a wide range of retail customers that use a broad portion of the total manifest, ultimately, to maximize returns to the grower.

- Some integrated operations also own and operate a sales desk.

- Successful packing warehouses must closely monitor sales-desk performance to ensure that competitive returns are realized on packed fruit.

- New technology, both in the field and in the warehouse, could reduce labor requirements substantially over the next five to 10 years. Specifically, such technology could include the use of platforms and mechanical harvest methods in the orchards or the increased use of robotics and digital-imaging sorters within the warehouses.

- Packing warehouses align with growers to assure their targeted product throughput.

- Integrated operations grow a significant portion of the fruit they pack.

- When working with retailers, value-added processes may prove to be a competitive differentiator. Such processes include inventory management, labeling, traceability programs, promotions and other value-enhancing activities.

- Warehouses with strong liquidity and lower leverage are able to weather adversity and take advantage of strategic opportunities.

- A business should assess the adequacy of its financial position annually by using tools such as financial ratios, peer financial benchmarks and historical trend analyses.

- Stress case scenarios may also be used to give an accurate picture of the true financial position of the business

Glossary

Bin. A container that holds 300 pounds of cherries.Bloom. A period that starts with the pink set and ends with petal fall about 10 days later. ‘Full bloom’ is defined as the day that 60% of ‘king blossoms’ are open on the north (shady) side of the tree.

Blossom thinning. Removing some of the blossoms that are turning to fruit.

Box. In the Northwest, a container that holds 20 pounds of cherries. In California, a box of cherries is 18 pounds.

Bud. Found in the axils (the upper angle between a leaf stalk or branch and the stem or trunk from which it is growing), a bud is basically a dormant and compressed shoot, which given the right conditions will resume growth.

Cambium. The thin layer of tissue, often green or greenish yellow, between the bark and the wood on a tree. It is important to line up the cambium in grafting between rootstock and scion.

Central leader. A tree where the main branch goes straight up the center.

Clone. A genetically identical group of plants derived and maintained from one individual by vegetative propagation.

Cold hardiness (hardy). The ability of plants to withstand cold injury (autumn-winter).

Cross pollination. Pollen moving from one flower to another, on the same plant or among flowers on different plants. Pollen moved between different plants often results in fruit that is different from either parent (i.e., a hybrid of the two).

Culls. Fruit that is discarded at the warehouse and will not go to market.

Cultivar. A plant variety that has been produced in cultivation by selective breeding.

Dormant. Describes the inactive or sleeping state in which a plant stops growing but is still alive.

Drip irrigation. Watering through soaker hoses or emitters placing water at plant bases on the soil surface; least wasteful method of watering.

Drip line. The rough circle that may be drawn on the ground around a tree where rain would drip off the outermost leaves. The most active roots are often located along this line.

Fresh. Fruits (or vegetables) that are harvested and sold without the intention of further processing. Generally, fresh fruits will be consumed raw or cooked by the consumer.

Frost damage. Cold-temperature injury during a stage of the growing season. Parts affected are flower buds, flowers and young fruit (spring) or near-mature fruit or other tissues (fall).

Fruiting wood. The smaller wood or spurs on which the fruit is actually grown.

GLOBALGAP. An internationally recognized set of farm standards dedicated to Good Agricultural Practices (GAP). Through certification, producers demonstrate their adherence to GLOBALGAP standards. For consumers and retailers, the GLOBALGAP certificate is reassurance that food reaches accepted levels of safety and quality, and has been produced sustainably, respecting the health, safety and welfare of workers and the environment, and in consideration of animal welfare issues. Without such reassurance, farmers may be denied access to markets.

Grafting. A way to propagate a plant by inserting a section of one plant (the scion) into another plant (the stock).

Hardiness. Ability of a plant to withstand temperature extremes; usually refers to cold hardiness.

High density. An area where more than 415 trees are planted per acre.

King blossom. The larger dominant blossom that is usually found in the center of the blossom cluster, surrounded by the yet unopened ‘side blossoms.’ The largest fruit will come from the king blossom.

Mildew. A grayish-white fungus disease found on the leaves, shoots and fruit.

Organic certification. Verifies that a farm or handling facility complies with USDA organic regulations. This certification allows the holder to sell, label and represent products as organic. Farms all over the world may be certified to the USDA organic standards. Most farms and businesses that grow, handle or process organic products must be certified.

Packouts. The number of boxes of fruit that can be packed out of a bin.

Packer. Company that owns the warehouse where cherries are packed, stored and shipped.

Pickers. Workers who pick tree fruit by hand, and carefully handle the fruit to ensure good quality. The picker wears a bucket that has a canvas bottom, held shut with a drawstring. When the bucket is full, the worker empties it into a wooden bin by releasing the string.

Pollination. The transfer of pollen from the male part of flowers (the anthers) to the female part (the stigma). Poor pollination results in a small fruit crop. In most tree fruit, the transfer is accomplished by insects. Because there are not enough wild bees to pollinate commercial orchards, growers place beehives throughout the orchard for 10 to 14 days during the bloom to ensure good pollination. Full bloom is when good pollination is essential.

Processing. Fruit that is not sent to the fresh market and is typically canned, sliced or juiced.

Pruning. The removal of living canes, shoots, leaves and other vegetative parts of the branch.

Rootstalk. Sometimes called “stock,” this is the root system (plant) propagated from seed (seedling) or vegetatively as common in clonal rootstocks on which various cultivars are budded or grafted. Many rootstocks are used and possess traits that relate to anchorage, size control, tolerance of light and heavy soils, “wet feet,” specific nematodes and other plants and diseases.

Marketing-sales desk. Sells and markets fruit on behalf of packers.

Scion. A detached stem, usually dormant, used in asexual propagation by grafting techniques.

Set. The amount of blossoms or fruit held on the tree.

Shoot. Wood that is usually not over 1 or 2 years old and is longer than the short, stubby spur growth.

Sleeping eye. Grown less than one year at the nursery. The rootstock is budded with the preferred variety in the fall. Before winter, the rootstock with its dormant bud is harvested, kept under optimal storage conditions, and then provided the next spring to the grower for establishment in the orchard. The grower is then responsible for training the tree resulting from growth of the bud, a step that is usually conducted at the nursery. This results in a lower outlay by the grower at this point in orchard establishment.

Sucker. A cane that emerges from below the bud union, and therefore comes from the rootstock rather than from the variety grafted onto it. On other plants, a sucker is any unwanted, fast-growing, upright growth from roots, trunk, crown or main branches.

Sunburn. The damage caused by the hot summer sun on the branches, “cooking” and destroying the bark and tissues.

Thinning. Removal of flower clusters, immature clusters or part of immature clusters. (See also ‘blossom thinning.’)

Training. Certain practices supplementary to pruning and necessary for shaping the vine.

Variety. Variety and ‘named variety’ are commonly used to mean the same as cultivar. Technically, a naturally occurring variant of a species.

Vigor. Refers to amount and rate of growth; relative among cultivars, climates and horticultural practices.

Stay up to date

Receive email notifications about Northwest and global and agricultural and economic perspectives, trends, programs, events, webinars and articles.

Subscribe